Find out whether wood ash is good for your garden. It can be used as a fertilizer and to make the soil less acidic.

How to Make a Wicking Bed

Grow Vegetables in Straw Bales

Home Garden Soil Contamination

By Steven Biggs

Understanding the Risk of Soil Contamination Around Your Home

AFTER MOVING INTO MY WORLD WAR I-ERA HOUSE, I decided to find out if the paint-chip-studded soil next to the house was safe for growing edible crops.

Many pre-1991 paints contained lead, and those that are pre-1960s—particularly exterior paints—are thought to be the worst culprits.

Lead was also used as a gasoline additive into the 1990s, meaning urban areas—home to old painted buildings, ample exhaust fumes and industrial emissions—tend to have higher soil lead levels than rural, agricultural areas.

With this in mind, I wanted to understand what, if any, risk lay hidden in my soil.

With an older house, I was worried about lead contamination from paint.

Conflicting Information

Yet the more I delved into the question of urban soil contamination, the less clear the issue became.

I found a government fact sheet saying there was minimal risk to consuming veggies grown in soil with lead levels below 200 parts per million (ppm)

But one from another jurisdiction advising 300 ppm.

Both noted increased risk for children (think soil moving hand to mouth), in which case one gave a safe upper limit of 100 ppm.

I was left wondering whether I should go with 100, 200 or 300 ppm.

So I Got on the Phone

When I called Ontario’s Ministry of the Environment, I was told that contaminant levels in typical agricultural soil are often less than urban areas, but there should be no concern as long as the readings for my soil fell below the residential standards, as set out in the provincial Environmental Protection Act. But…I should also keep in mind that a reading above that residential level isn’t necessarily unsafe.

Understanding soil contamination was starting to seem as fun as doing my tax return.

So, after scanning the Act, I added 45 ppm lead (for typical agricultural soil), 120 ppm lead (for residential standards), and a big question mark (for “isn’t necessarily unsafe”) to my growing list of values.

This was getting to be as much fun as preparing a tax return!

And just as filling in a tax return isn’t black and white—think of deciding what’s tax deductible and what’s not—I sensed balancing soil contamination and growing edibles had shades of grey, too.

So I set out to see how urban veggie growers can best tackle the question of soil contamination without being mired in conflicting numbers.

What Other Growers Do

Travis Kennedy, an agrologist involved in community garden projects, also raises produce at his Lactuca Micro Farm in Edmonton. “Pragmaculture,” he responds with a laugh, when I ask how he deals with possible soil contamination. His pragmatic approach to urban agriculture is to always use raised beds, bringing in soil he knows is safe, because he always assumes that there may be contamination.

Ward Teulon, also an agrologist, runs City Farm Boy in Vancouver, designing and building vegetable gardens. Teulon explains that sending backyard soil samples to a laboratory doesn’t always give a clear picture of what’s in the soil because urban soils are moved around a lot and are not uniform. He agrees, however, that interpreting results from expensive tests, which can cost hundreds of dollars, can be daunting. If there is a cause for concern, he believes money is better spent bringing in soil to make a raised bed. “Find out your property’s history,” he advises, because many urban soils are perfectly fine.

Luckily for me, my property’s history seems clear-cut, from agricultural to residential.

So, aside from the paint-chip-infested soil beside the house, I’m not worried. Gardeners who don’t know the history of their site could ask neighbours about past use and nearby properties, or check municipal records or archives.

Asssessing the Risk

In 2014 Toronto Public Health created a plain-language guide to help gardeners understand the issues surrounding possible soil contamination and growing edibles.

Josephine Archbold, who helped write the Guide for Soil Testing in Urban Gardens, says it’s wrong to think only experts can figure out when to grow and when to worry.

The guide moves away from the notion that soil is either safe or unsafe—a black-and-white approach.

“I think we need to move beyond the concept of ‘safe’ and ‘not-safe’ cut-off levels that tell gardeners to either garden (100 per cent) or not garden at all (0 per cent),” she says. Instead, the guide is intended to help gardeners think about the risk of contamination for a site, and gives options to deal with the situation. Testing is expensive, and raised beds can be expensive, too, so the guide encourages taking such actions only when the risk of contamination makes them appropriate.

Former orchard land is among those sites considered medium concern because of the legacy of old metal-containing sprays.

Three-Step Guide

Step 1

In the three-step guide, the first step is to establish a level of concern by looking at former land use. With high-concern sites (e.g., former gas stations), contamination is very likely, so the guide recommends skipping expensive tests and using risk-minimizing measures such as raised beds, container gardening, or cultivating fruit and nut trees—for which contaminant uptake isn’t a concern. Nor is soil testing recommended for low-risk sites (e.g., long-term residential areas).

There are medium-concern situations (e.g., hydro corridors and former commercial land) where testing is recommended, but even then, if gardens are smaller than 170 square feet (16 sq. m), raised beds are suggested because the cost of raised beds for such a surface area is likely less than testing. Surprisingly, former orchard land is among those sites considered medium concern because of the legacy of old metal-containing sprays.

After investigating the history of the garden site, another part of establishing a level of concern is physically inspecting soil: dig in a few random spots to see if there are unusual stains or odours, and note old equipment, tanks and debris that might provide clues to dumping. Dumping, burning, smells and staining can make for a high-concern site.

Step 2

When it comes to step two, testing the soil, the guide lists common contaminants, including some metals (such as lead, arsenic and cadmium), along with PAHs (polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons), which Archbold explains are compounds that indicate past industrial activity. “Our soil screening values are specifically for urban gardening,” she says.

Step 3

The third step is to take actions to reduce risk. In keeping with the guide’s approach, the screening values don’t tell gardeners to either garden or not garden. The values help guide the actions of gardeners. For example, if test results or site history present a medium concern, suggested tactics are lowering the level of contaminants by adding clean soil and organic matter. Archbold says adding organic matter makes many contaminants less mobile.

Another example of how to reduce risk is reducing soil dust by covering soil with a mulch, peeling root vegetables before eating and avoiding crops more likely to accumulate contaminants (cabbage family, beets and spinach).

Suspect Contamination?

If you suspect contamination and opt for testing instead of raised beds, containers, or fruit and nut trees, the guide gives pointers about how to find an accredited lab in your area. When collecting soil samples, there are some important steps to follow—and the guide gives instructions for this as well.

As for the strip beside my house, I will plant a fruit tree. I still don’t know how many parts per million lead are in the soil there, but because the site inspection (namely, digging and seeing all those paint chips) points to a possibility of contamination, my guess is that lead levels could be on the high side. It’s a very small space, so I’ve ruled out expensive testing.

I’ve also ruled out a raised bed because I don’t want to redirect water into my neighbour’s yard. So, a fruit tree seems to me to be the most practical approach—and is an acceptable shade of grey for me.

Originally published in Garden Making Magazine, Spring 2014

What to do with Pumpkins After Halloween (and a Pumpkin Recipe!)

By Steven Biggs

Cook (or Compost) Your Pumpkins Too!

The first pumpkin is carved for Halloween this year; the kids had a pumpkin-carving get-together with friends over the weekend. That only leaves three giant pumpkins, four pie pumpkins, a warty pumpkin, a Jamaican pumpkin, a Turk’s turban squash, a blue hubbard squash, and an elongated pinkish pumpkin. Guess what we’re doing tomorrow!

We’ve hit a pumpkin-carving crescendo this year. The kids are the right age to design and carve. I love it as much as my they do. (To my imagination that blue hubbard squash looks a bit like a turkey in a roasting pan…)

Did we go overboard with so many pumpkins and squash? No.

Pumpkins make their way into our kitchen, or into our soil. We eat them or compost them.

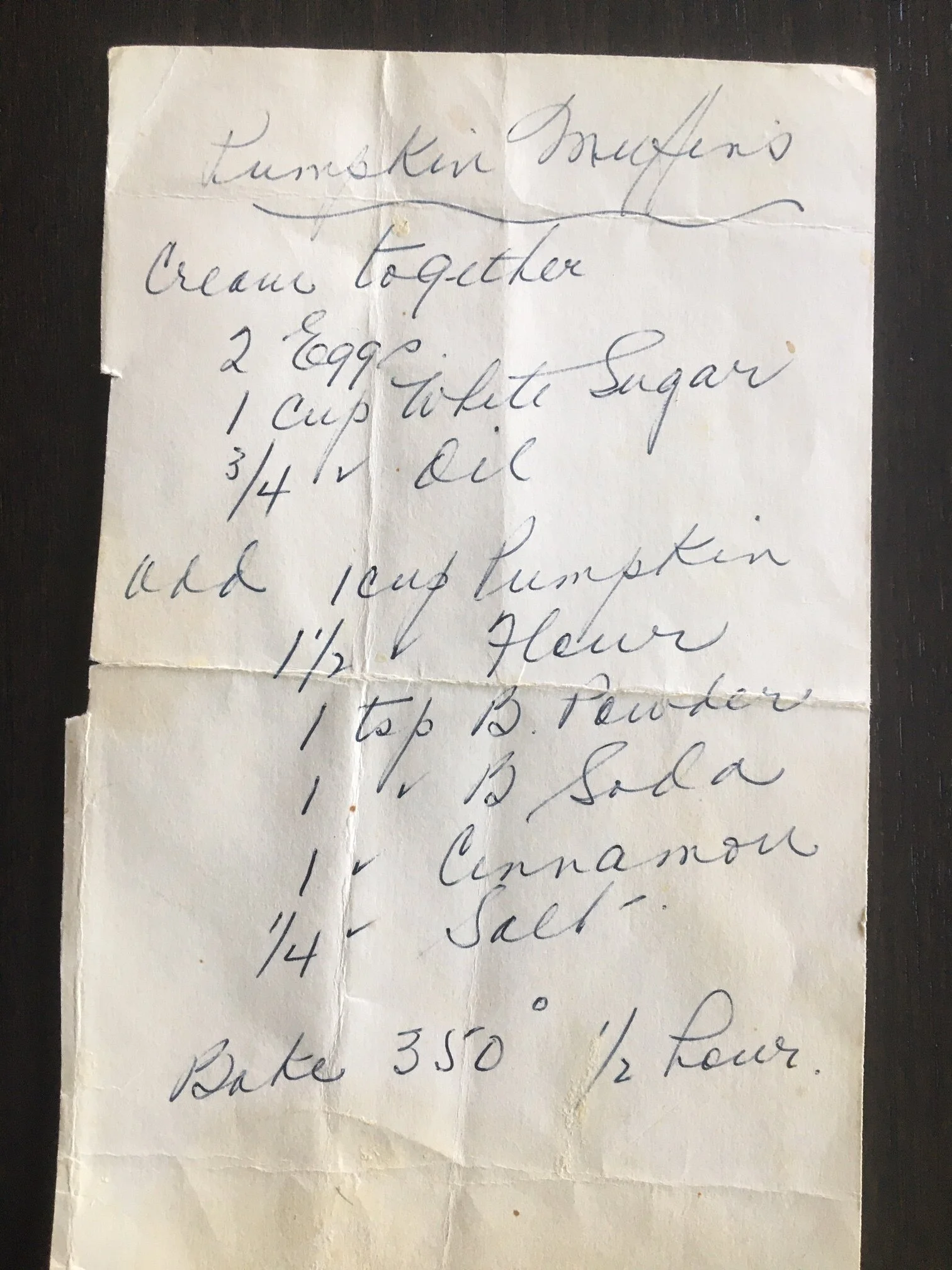

Pumpkin Muffins

Nana Biggs’ pumpkin muffin recipe. (I usually cut the sugar in half and add raisins and nuts.)

One of Nana Biggs’ favourite recipes was pumpkin muffins. I remember as a kid taking my jack-o-lantern there the day after Halloween so that Nana could roast it.

(My Uncle Bill didn’t agree with my giving Nana all of that pumpkin as he didn’t care for the supply of muffins encouraged by it. I never let him forget that. One fall after I had moved away from home, I roasted a jack-o-lantern, baked a giant, six-inch-wide muffin, and sent it to Uncle Bill by courier.)

My kids all like pumpkin muffins, so Nana would be pleased. They love roasted pumpkin seeds too. (A bit of oil, salt, and garlic powder makes a mean roasted pumpkin seed, in my opinion.)

Last year, my wife, Shelley, spent a whole day roasting various pumpkins and squash, and made a series of pies, using different proportions of each. We got to taste-test them all. There were lots more that went into the freezer. We just ate the last one yesterday.

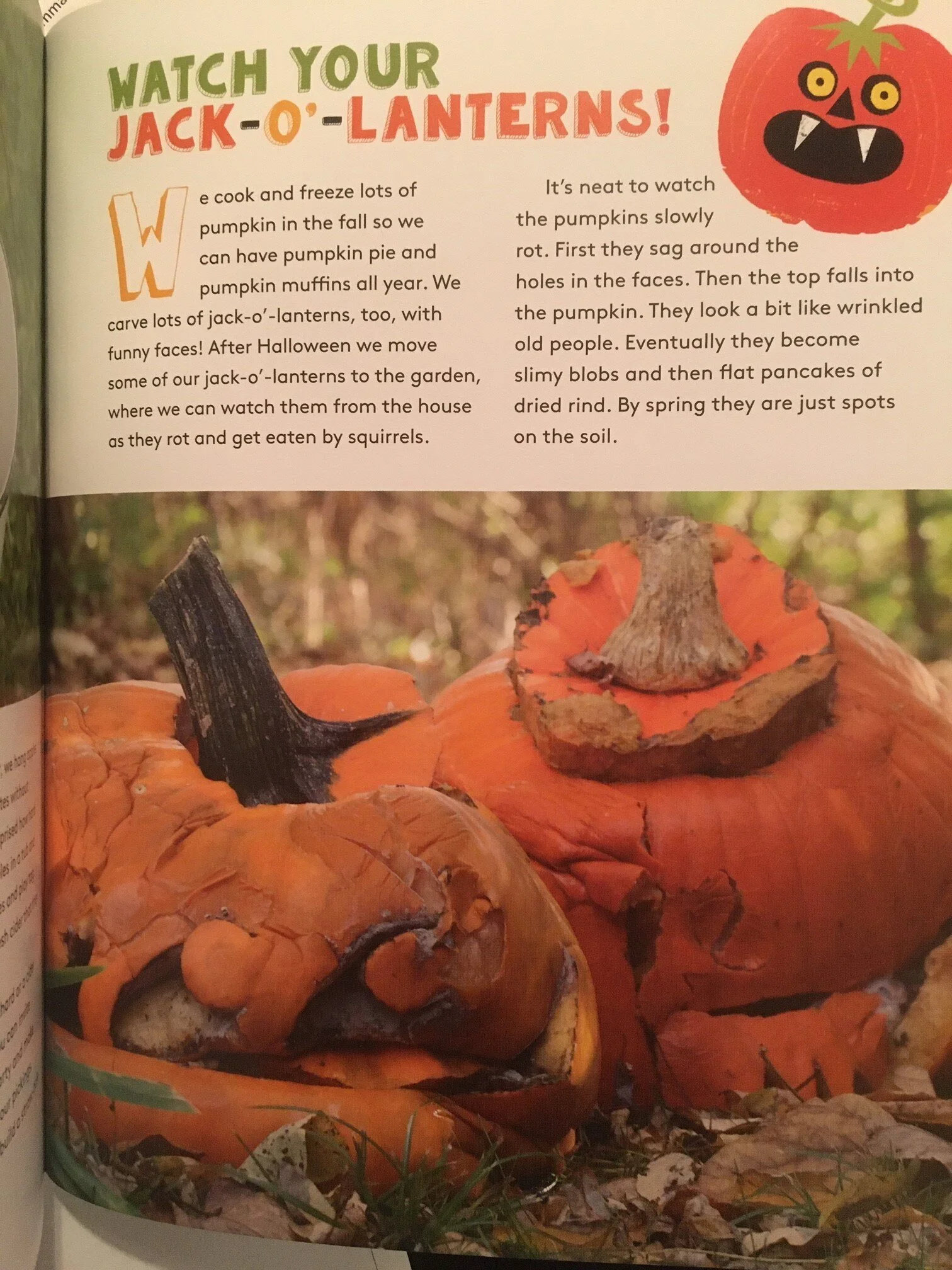

Watch Your Jack-O-Lanterns!

In my daughter Emma’s book, Gardening with Emma, she tells kids how pumpkins in the garden start to sag, and then become spots on the soil by spring.

You must be wondering if we’ll eat all of those pumpkins on our front porch this year. We’ll use the pie pumpkins first, as they have a less watery, more flavourful flesh.

What doesn’t go into pumpkin pies, muffins, and soups feeds the soil. My daugher Emma shares this idea in her book Gardening with Emma.

Sometimes we put our jack-o-lanterns in the compost pile. But what’s really fun is watching them slowly melt into the soil.

Each one ages differently!

Written for kids by a kid, this guide helps kids see the fun side of gardening, whether it’s growing giant vegetables, making a bug vacuum, or making a sound-themed garden.

Emma shares lots of inspiring ideas for young gardeners about how to grow healthy food, raise cool plants, and have fun outdoors.

Copies from the Food Garden Life shop are signed by Emma!